Volume 372, Issue 24, 9 June 2008, Pages 4344-4349

Roman

Tomaschitz ,

a,

,

a,

Abstract

Tachyonic spectral densities of ultra-relativistic electron populations are fitted to the γ-ray spectra of two TeV blazars, the BL Lacertae objects 1ES 0229+200 and 1ES 0347-121. The spectral maps are compared to Galactic TeV sources, the γ-ray binary LS 5039 and the supernova remnant W28. In contrast to TeV photons, the extragalactic tachyon flux is not attenuated by interaction with the cosmic background light; there is no absorption of tachyonic γ-rays via pair creation, as tachyons do not interact with infrared background photons. The curvature of the observed γ-ray spectra is intrinsic, caused by the Boltzmann factor of the electron densities, and reproduced by a tachyonic cascade fit. In particular, the curvature in the spectral map of the Galactic microquasar is more pronounced than of the two extragalactic γ-ray sources. Estimates of the thermodynamic parameters of the thermal or, in the case of supernova remnant W28, shock-heated nonthermal electron plasma generating the tachyon flux are obtained from the spectral fits.

Keywords: Superluminal radiation; Tachyonic cascade spectra; Ultra-relativistic electron plasma; TeV blazars; Spectral averaging; Proca equation with negative mass-square

PACS classification codes: 03.50.Kk; 05.30.Fk; 52.27.Ny; 95.30.Gv

Article Outline

1. Introduction

The goal is to point out evidence for superluminal γ-rays from two active galactic nuclei, the BL Lacertae objects 1ES 0229+200, cf. Refs. [1], [2], [3] and [4], and 1ES 0347-121, cf. Refs. [5], [6] and [7]. Spectral maps of these TeV blazars have recently been obtained by means of ground-based imaging air Cherenkov detectors [4] and [7]. Here, a tachyonic cascade fit is performed to the γ-ray spectrum of these blazars. In contrast to electromagnetic γ-rays, tachyons cannot interact with infrared background photons, so that there is no attenuation of the extragalactic tachyon flux by electron–positron pair production. The observed spectrum is already the intrinsic one without any need of absorption correction as required in electromagnetic spectral fits [8] and [9]. The spectral curvature is generated by the Boltzmann factor of the thermal electron plasma in the galactic nuclei.Tachyonic cascade spectra are obtained by averaging the superluminal spectral densities of individual electrons with ultra-relativistic Fermi distributions. We use the averaged radiation densities to perform spectral fits to the γ-ray spectra of the mentioned BL Lacertae objects as well as the microquasar LS 5039 and the supernova remnant W28. Tachyonic cascade spectra generated by thermal electron populations in the active galactic nuclei (AGNs) provide excellent fits to the observed γ-ray flux. The temperature, source count, and internal energy of the ultra-relativistic electron plasma are obtained from the spectral fits. The spectral map of the Galactic microquasar is no less curved than the cascades in the AGN spectra. Moreover, the spectral curvature of the AGNs does not increase with increasing redshift, which is further evidence for an unattenuated extragalactic γ-ray flux.

The tachyonic radiation field is a Proca field with negative

mass-square,

In Section 2, we further elaborate on the tachyonic Proca equation by comparing to electromagnetic theory, and assemble the tachyonic spectral averages employed in the fits, which are based on the transversal and longitudinal radiation densities generated by a free electronic spinor current. In Section 3, the spectral fitting is explained, and intrinsic spectral curvature is argued by comparing the cascade spectra of the above-mentioned Galactic and extragalactic TeV sources. The conclusions are summarized in Section 4.

2. Spectral maps in the γ-ray bands: Origin and structure of tachyonic cascade spectra

The Lagrangian (1) resembles

its electrodynamic counterpart, but the negative mass-square of the

Proca field causes striking differences. Apart from the superluminal

speed of the tachyonic quanta, the radiation is partially

longitudinally polarized [12], the gauge

freedom is broken, and freely propagating charges can radiate

superluminal quanta. The analogy to Maxwell's theory becomes even more

transparent in 3D. The tachyonic E and B

fields are related to the vector potential Aα=(A0,A)

by E= A0−∂A/∂t

and B=rotA,

and the field equations decompose into

A0−∂A/∂t

and B=rotA,

and the field equations decompose into

The spectral fits in Section 3 are based on

the quantized tachyonic radiation densities

=c=1

can easily be restored. We use the Heaviside–Lorentz system, so that αq=q2/(4π

=c=1

can easily be restored. We use the Heaviside–Lorentz system, so that αq=q2/(4π c)≈1.0×10−13

and mt≈2.15

keV/c2; the

tachyon–electron mass ratio is mt/m≈1/238.

These estimates are obtained from Lamb shifts of hydrogenic ions [16]. A spectral

cutoff occurs at

c)≈1.0×10−13

and mt≈2.15

keV/c2; the

tachyon–electron mass ratio is mt/m≈1/238.

These estimates are obtained from Lamb shifts of hydrogenic ions [16]. A spectral

cutoff occurs atOnly frequencies in the range 0

ω

ω ωmax(γ)

can be radiated by a uniformly moving electron, the tachyonic spectral

densities pT,L(ω,γ)

being cut off at the break frequency ωmax.

A positive ωmax(γ)

requires Lorentz factors exceeding the threshold μt

in (4), since ωmax(μt)=0.

The lower threshold on the speed of the electron for radiation to occur

is thus υmin=mt/(2mμt).

The tachyon–electron mass ratio gives υmin/c≈2.1×10−3,

which is roughly the speed of the Galaxy in the microwave background [17].

ωmax(γ)

can be radiated by a uniformly moving electron, the tachyonic spectral

densities pT,L(ω,γ)

being cut off at the break frequency ωmax.

A positive ωmax(γ)

requires Lorentz factors exceeding the threshold μt

in (4), since ωmax(μt)=0.

The lower threshold on the speed of the electron for radiation to occur

is thus υmin=mt/(2mμt).

The tachyon–electron mass ratio gives υmin/c≈2.1×10−3,

which is roughly the speed of the Galaxy in the microwave background [17].

The radiation densities (3) refer to a

single spinning charge with Lorentz factor γ; we

average them with a Fermi power-law distribution [18] and [19],

δ

δ 4.

Otherwise, there are no conceptual constraints on the power-law index

of these stationary non-equilibrium distributions. Thermal equilibrium

is recovered with δ=0

and γ1=1;

the spectral fits of the blazars and the microquasar in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 are

performed with equilibrium distributions. The shocked electron plasma

of supernova remnant W28 requires δ≈3.6

to fit the steep power-law slope in Fig. 4. The

exponent

4.

Otherwise, there are no conceptual constraints on the power-law index

of these stationary non-equilibrium distributions. Thermal equilibrium

is recovered with δ=0

and γ1=1;

the spectral fits of the blazars and the microquasar in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 are

performed with equilibrium distributions. The shocked electron plasma

of supernova remnant W28 requires δ≈3.6

to fit the steep power-law slope in Fig. 4. The

exponent

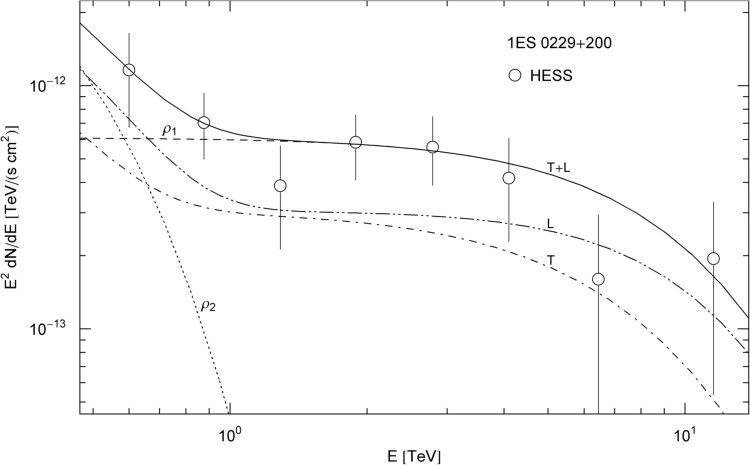

Fig. 1. Spectral map of the BL Lac 1ES 0229+200. HESS data points from [4]. The solid line T+L depicts the unpolarized differential tachyon flux dNT+L/dE, obtained by adding the flux densities ρ1,2 of two electron populations, cf. (16) and Table 1. The transversal (T, dot-dashed) and longitudinal (L, double-dot-dashed) flux densities add up to the total unpolarized flux T+L. The exponential decay of the cascades ρ1,2 sets in at about Ecut≈(mt/m)kT, implying cutoffs at 3.6 TeV for the ρ1 cascade and 120 GeV for ρ2.

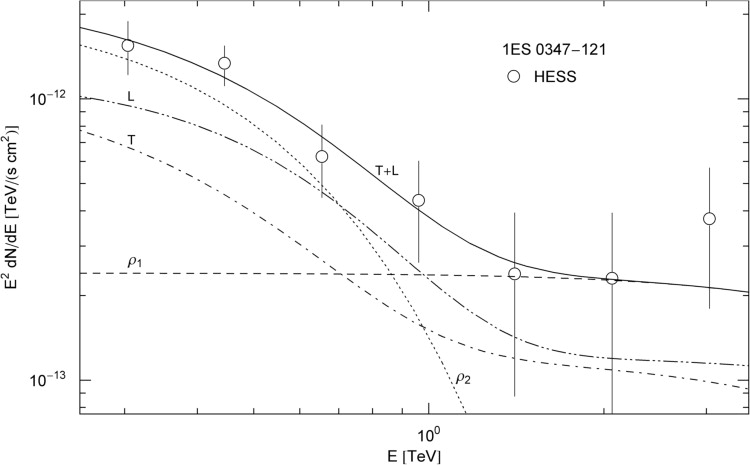

Fig. 2. Spectral map of the BL Lac 1ES 0347-121. HESS

points from [7]. The

unpolarized spectral fit T+L is based on the electron distributions

recorded in Table 1, the

polarized flux components are labeled T and L. The ρ1

cascade is cut at Ecut≈4.0

TeV, and ρ2

at 190 GeV. The curvature in the spectral slope of 1ES 0347-121 at z≈0.188

is less pronounced than of 1ES 0229+200 at z≈0.140,

suggesting that the shape of the rescaled flux density ![]() is intrinsic rather than generated by intergalactic absorption.

is intrinsic rather than generated by intergalactic absorption.

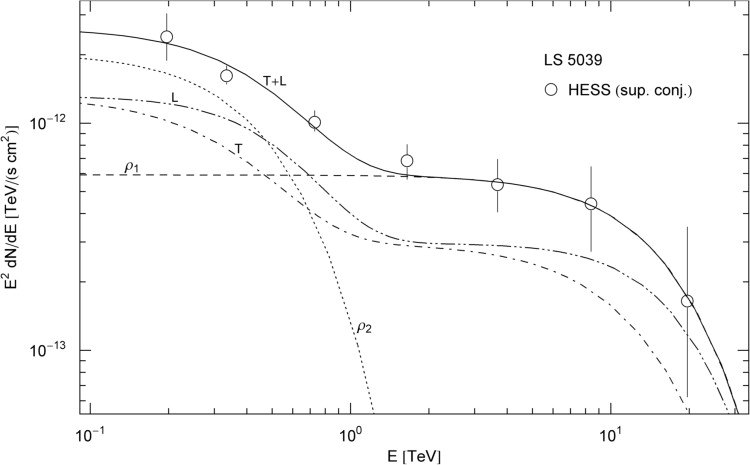

Fig. 3. Spectral map of the γ-ray binary LS 5039 close to periastron. HESS data points at the superior conjunction [32]. Notation as in Fig. 1. The cascade ρ1 is exponentially cut at Ecut≈6.3 TeV, and ρ2 at 190 GeV, cf. Table 1. The spectral map of this microquasar at a distance of 2.5 kpc is more strongly curved than of the AGNs in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, indicating that the curvature of the AGN spectra is intrinsic as well, generated by the Boltzmann factor of the thermal electron populations, cf. caption to Fig. 2.

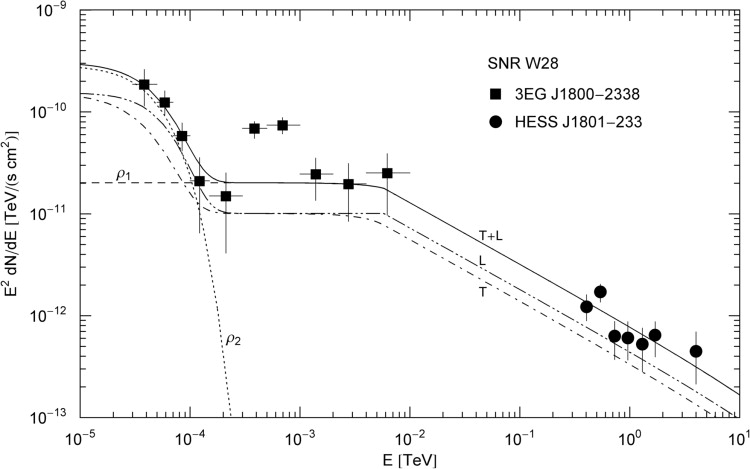

Fig. 4. γ-Ray broadband of the TeV source HESS J1801-233 and the associated EGRET source 3EG J1800-2338 at the northeast boundary of supernova remnant W28. Data points from [35], also see [36] and [37]. Notation as in Fig. 1. The nonthermal cascade ρ1 admits a power-law slope ∝E1−α, α≈1.6, adjacent to the MeV–GeV plateau typical for tachyonic cascade spectra [11] and [12]. A spectral break at mtγ1≈5.8 GeV is visible as edge in the longitudinal component. The curvature of the thermal cascade ρ2 in the MeV range is due to the exponential cutoff at (mt/m)kT≈20 MeV, cf. Table 1.

The spectral average of the radiation densities (3) is carried

out as

The average (6) can be

reduced to the fermionic spectral functions

μt,

cf. after (4). This

threshold Lorentz factor γ1

defines the break frequency,

μt,

cf. after (4). This

threshold Lorentz factor γ1

defines the break frequency,which separates the spectrum into a low- and high-frequency band [30]. By making use of the spectral functions (8), we can write the averaged radiation densities (6) as

with

where the weight factors fk read

with density dρF(γ) in (5).

The quasiclassical fugacity expansion of the spectral

functions (11) is found by

expanding density (5) in ascending

powers of ![]() .

In leading order, dρF(γ)

.

In leading order, dρF(γ) dρα,β(γ),

dρα,β(γ),

Aα,ββδ−kΓ(k−δ,βγ1),

obtained by replacing the fermionic dρF

in the weights (12) by the

Boltzmann power-law density (13).

Aα,ββδ−kΓ(k−δ,βγ1),

obtained by replacing the fermionic dρF

in the weights (12) by the

Boltzmann power-law density (13).

The classical limit of the fermionic spectral functions FT,L(ω,γ1)

in (8) is the

Boltzmann average [31]

pT,L(ω)

pT,L(ω) F

in (10) thus reads

F

in (10) thus readswhere

3. Spectral curvature of Galactic and extragalactic TeV γ-ray sources: Does distance matter?

The spectral fits of the active galactic nuclei (AGNs) and the

Galactic TeV sources in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 are based

on the E2-rescaled

flux densities

pT,L(ω)

pT,L(ω) α,β

the spectral average (15) (with ω=E/

α,β

the spectral average (15) (with ω=E/ ).

The fits are done with the unpolarized flux density dNT+L=dNT+dNL

of two electron populations ρi=1,2,

cf. Table 1. Each

electron density generates a cascade ρi,

and the wideband comprises two cascade spectra labeled ρ1

and ρ2

in the figures. As for the electron count,

).

The fits are done with the unpolarized flux density dNT+L=dNT+dNL

of two electron populations ρi=1,2,

cf. Table 1. Each

electron density generates a cascade ρi,

and the wideband comprises two cascade spectra labeled ρ1

and ρ2

in the figures. As for the electron count, which is independent of the distance estimate in (16). Here,

cz/H0,

with the Hubble distance c/H0≈4.4×103

Mpc (that is, h0≈0.68).

Hence, d[Mpc]≈4.4×103z,

and

cz/H0,

with the Hubble distance c/H0≈4.4×103

Mpc (that is, h0≈0.68).

Hence, d[Mpc]≈4.4×103z,

and Electronic source distributions ρi

generating the tachyonic cascade spectra of the active galactic nuclei

in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, the

microquasar LS 5039 in Fig. 3, and the

supernova remnant W28 in Fig. 4. Each ρi

stands for a thermal Maxwell–Boltzmann density dρα=−2,β(γ)

with γ1=1,

apart from the ρ1

distribution of SNR W28, which is a power-law density with α≈1.6

and γ1≈2.7×106,

cf. (13) and after (5). β

is the cutoff parameter in the Boltzmann factor. ![]() determines the amplitude of the tachyon flux generated by the electron

density ρi,

from which the electron count ne

is inferred at the indicated distance d, cf. after (17). kT

is the temperature and U the internal energy of the

electron populations, cf. after (16). The

parameters β and

determines the amplitude of the tachyon flux generated by the electron

density ρi,

from which the electron count ne

is inferred at the indicated distance d, cf. after (17). kT

is the temperature and U the internal energy of the

electron populations, cf. after (16). The

parameters β and ![]() are extracted from the least-squares fit T+L in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4

are extracted from the least-squares fit T+L in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4

| β | d | ne | kT (TeV) | U (erg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1ES 0229+200 | z≈0.140 | |||||

| ρ1 | 5.97×10−10 | 6.6×10−5 | 620 Mpc | 1.4×1057 | 860 | 5.8×1060 |

| ρ2 | 1.79×10−8 | 7.5×10−4 | 1.6×1058 | 29 | 2.2×1060 | |

| 1ES 0347-121 | z≈0.188 | |||||

| ρ1 | 5.38×10−10 | 2.6×10−5 | 830 Mpc | 1.0×1057 | 950 | 4.6×1060 |

| ρ2 | 1.13×10−8 | 2.3×10−4 | 8.9×1057 | 45 | 1.9×1060 | |

| LS 5039 (sup. conj.) | 2.5 kpc | |||||

| ρ1 | 3.36×10−10 | 6.4×10−5 | 2.3×1046 | 1500 | 1.7×1050 | |

| ρ2 | 1.13×10−8 | 2.2×10−4 | 7.9×1046 | 45 | 1.7×1049 | |

| SNR W28 | 1.9 kpc | |||||

| ρ1 | – | 2.2×10−3 | 4.6×1047 | – | – | |

| ρ2 | 1.08×10−4 | 3.1×10−2 | 6.4×1048 | 4.7×10−3 | 1.5×1047 |

Fig. 1 shows the tachyonic spectral map of the BL Lacertae object (BL Lac) 1ES 0229+200, located at a redshift of z≈0.140, cf. Refs. [1], [2], [3] and [4]. The flux points were obtained with the HESS array of atmospheric Cherenkov telescopes in the Khomas Highland of Namibia [4]. The χ2-fit is done with the unpolarized tachyon flux T+L, and subsequently split into transversal and longitudinal components. The differential flux is rescaled with E2 for better visibility of the spectral curvature. Temperature and source count of the electron populations generating the cascades are recorded in Table 1. In Fig. 2, we show the spectral map of the BL Lac 1ES 0347-121, at a redshift of z≈0.188, cf. Refs. [5], [6] and [7]. TeV γ-ray spectra of BL Lacs are usually assumed to be generated by inverse Compton scattering or proton–proton scattering followed by pion decay [8]. Both mechanisms result in a flux of TeV photons, assumed to be partially absorbed by interaction with infrared background photons owing to pair creation, so that the intrinsic spectrum has to be reconstructed on the basis of intergalactic absorption models depending on vaguely known cosmological input parameters [9]. The extragalactic tachyon flux is not attenuated by interaction with the background light, there is no absorption of tachyonic γ-rays. The superluminal Proca field (1) is minimally coupled to the electron current, and does not directly interact with electromagnetic radiation.

The spectral curvature apparent in double-logarithmic plots of the E2-rescaled flux densities (16) is intrinsic, caused by the Boltzmann factor of the electron populations generating the tachyon flux. The curvature present in TeV γ-ray spectra does not increase with distance, at least there is no evidence to that effect if we compare the spectral slopes of the blazars in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, and the spectral maps of other flaring AGNs such as H1426+428 at z≈0.129 and 1ES 1959+650 at z≈0.047, cf. Ref. [11]. Further evidence for intrinsic spectral curvature is provided by Fig. 3, depicting the spectral map of the microquasar LS 5039, a compact object orbiting a massive O-star [32], [33] and [34]. The spectral curvature of this Galactic binary is even more pronounced than of the BL Lacs in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. The same holds true for the HESS spectral map of LS 5039 at the inferior conjunction studied in Ref. [18].

Fig. 4 depicts the γ-ray wideband of the TeV source HESS J1801-233 and the coincident EGRET point source 3EG J1800-2338 [35], [36] and [37]. The extended TeV source is located on the northeastern rim of the supernova remnant (SNR) W28, a mixed-morphology SNR interacting with molecular clouds [38] and [39]. The spectral map of SNR W28 in Fig. 4 is to be compared to the unpulsed γ-ray spectrum of the Crab Nebula, cf. Fig. 1 in Ref. [11], the spectral map of SNR RX J1713.7-3946 in Fig. 2 of Ref. [11], and in particular to the unidentified TeV source TeV J2032+4130 in conjunction with the associated EGRET source 3EG J2033+4118, cf. Fig. 6 of Ref. [12]. A spectral plateau in the MeV to GeV range occurs frequently in spectral maps of TeV γ-ray sources, and can easily be fitted with tachyonic cascade spectra, in contrast to electromagnetic inverse-Compton fits. SNR W28 is located at a distance of 1.9 kpc [38]. The thermal cascade in the MeV range (ρ2 in Fig. 4) preceding the spectral plateau is strongly curved; the power-law slope of the ρ1 cascade also terminates in exponential decay, but outside the presently accessible TeV range shown in the figure. The cutoff temperature of the nonthermal electron density generating cascade ρ1 is too high to bend the power-law slope in the TeV range covered in Fig. 4, so that the internal energy of the shock-heated plasma could not be determined from the χ2-fit, in contrast with the power-law index α and the threshold Lorentz factor γ1, cf. caption to Table 1.

4. Conclusion

The spectral maps of two TeV γ-ray blazars have been fitted with tachyonic cascade spectra and compared to a Galactic γ-ray binary and supernova remnant. Table 1 contains estimates of the thermodynamic parameters of the electron populations generating the superluminal cascades. The spectral curvature is intrinsic and reproduced by the tachyonic spectral densities (3) averaged with ultra-relativistic thermal electron distributions, cf. Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. The shocked electron plasma in SNR W28 requires a nonthermal power-law distribution to adequately reproduce the TeV cascade in Fig. 4. The curvature in the γ-ray spectra of BL Lacs is uncorrelated with distance, so that absorption of electromagnetic radiation due to interaction with infrared photons is not an attractive explanation of spectral curvature. By contrast, there is no attenuation of the extragalactic tachyon flux, as tachyons cannot interact with cosmic background photons, so that the observed cascades are the intrinsic spectrum. The distance of the AGNs does not show in the spectral curvature, as tachyonic cascades are unaffected by background photons.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the support of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The hospitality and stimulating atmosphere of the Centre for Nonlinear Dynamics, Bharathidasan University, Trichy, and the Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Chennai, are likewise gratefully acknowledged.